Why I May or May Not Go to Burning Man Next Year: Reflections of a Virgin Burner

/Reading time: 10 minutes, 2000 words

The surest way to give something appeal is to pronounce it taboo. So when I first read of Burning Man nearly fifteen years ago, I wanted to participate. Scandalous festivities in a remote desert, governed only by the hedonistic participants themselves, seemed a pathway to transcendence, a veritable yellow brick road, maybe even the Land of Oz itself, or, if not that, at least an opportunity to gain a strong and long high on powerful drugs and orgiastic sex. But for all the promise I glimpsed in the media’s description of Burning Man, which was infinitesimal compared to the coverage today, debauchery was the cry. Alas, what the sheep lambaste, the living chase.

The challenge for those who live for such highs is planning. At least, that is my challenge. When I first learned of Burning Man I was twenty-something and had adopted as my life motto a witty (now politically incorrect) one-liner I’d read somewhere: try everything at least once, except homosexuality. (It’s not that I’m opposed to homosexuality, but I have no desire for it either.) So I carried on, hunting overstimulation in whatever shiny packaging it came in—minus sexy boys—and Burning Man became a distant oasis on the horizon, always forgotten, except when summer waned and I was reminded not only of the dawning of the event, but also of the unlikelihood of attending it in haste.

Perhaps it’s for the best. My former, less mature self would’ve shown up in a tank top and Converse, with a fistful of condoms and a can-do smirk. The heralded all-inclusive community might not have thrown me out, as club bouncers so gleefully did to me back then, but they might’ve thought twice before knighting me with a playa name and inviting me back. Maybe it was attendees like I would’ve been that caused Burning Man co-founder Larry Harvey to draft the Ten Principles in 2004, which include “radical self-reliance” and “civic responsibility.” To be radically self-reliant in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert requires foresight, something I possess in limited quantity.

Just three weeks before Burning Man opened its gates this year, as the media first began taunting me in my social feeds, I bought my ticket. I spent the next fortnight poring over pack lists and racing to hardware and sporting goods stores and home again to set up, test, and modify my gear—because most outfitters don’t manufacture their goods to withstand alkali powder storms and 50-knot winds accompanied by searing and freezing temps. Then I made the trips again, and again, and again, because, well, diminished foresight. Then my leaky ‘92 Jeep Cherokee choked. I considered selling my ticket, but I couldn’t stomach the idea of foregoing my dream another year, so instead I replaced my old Jeep with another old Jeep, a 1998. I insured and registered it just days before leaving. Having spent enough money to fund a tour of Europe, I was now committed, ready or not.

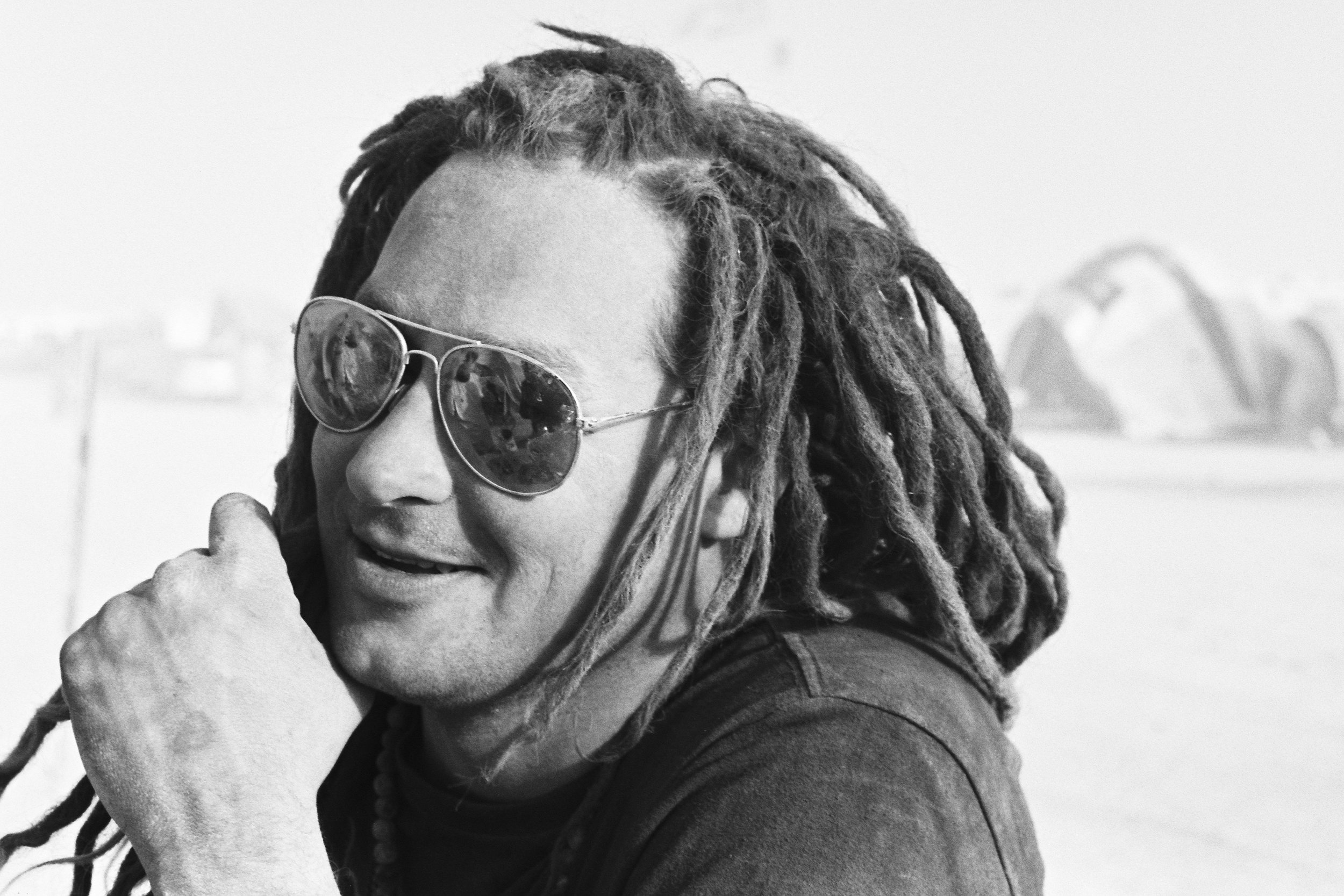

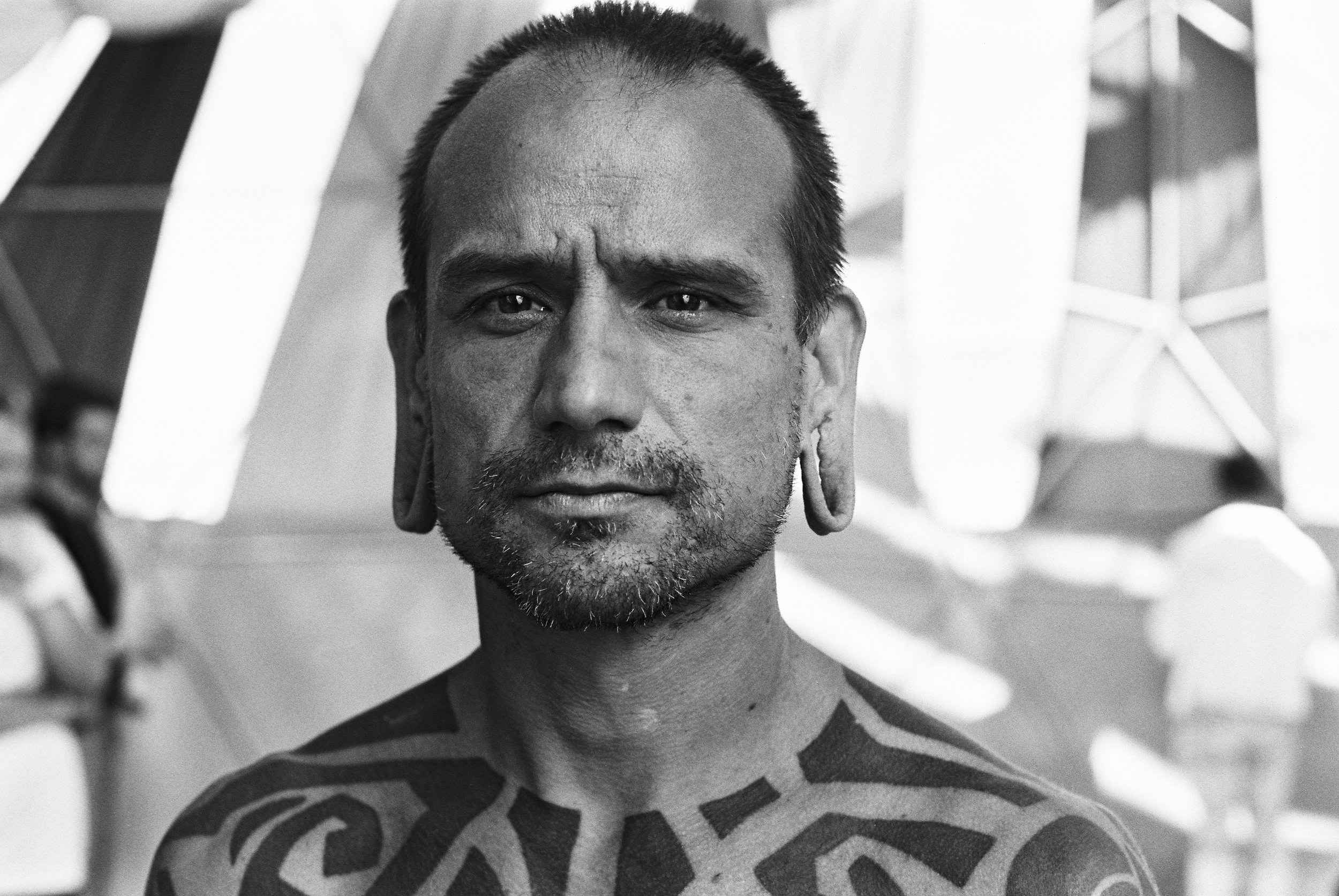

Being older now, and debatably more cultivated, my interests in Burning Man have evolved. Although I was still lured there by the prospect of rapture through revelry, I also wanted to experience Black Rock City’s gift economy, radically inclusive community, and the apparently free exchange of love and esoteric wisdom. For all that Burning Man is decried, it is also lauded as a utopia of sorts, a civilization manifested by the uncompromising vision and foolhardy work ethic of artists and dissidents (aka “burners”). Half of me hoped to find Burning Man’s gates pearlescent, and half of me intended to make a cultural study, as well as to make black-and-white portraits.

My dreams of exaltation began to fade, however, when upon choosing my campsite at Black Rock City I wasn’t greeted with hugs from naked women, but a “Hey, you parked a little close there” from my new neighbor, a youthful 50-year-old retiree from San Jose. “My bad,” I quipped. “I thought of asking first, but this is Burning Man. We’re all in this together, right?” He chuckled and we shook hands, and after determining there was sufficient space for a vehicle to pass between us, he returned to his tent porch. I cracked a beer, finished setting camp, and rode my bike out onto the playa in search of liberation. When the sun woke me the next morning, just twelve hours after having arrived at Burning Man, I contemplated leaving.

Where was the gloried Promised Land? Where was my joyous absolution? I saw costumes, lights, music, and the greatest concentration of beautiful people I had ever seen, but for all that I felt like I was at any mountain music fest, where good vibes and sweet intoxicants lube social camaraderie. My initial impression was that the only thing Burning Man has that other festivals do not is size.

But because I was eighteen hours older and three thousand dollars poorer for having made the pilgrimage, I decided to stay.

During my five-day campout I saw the remnants of a golden age of Burning Man, and I saw the gentrification of a culture, resulting from the influx of Millennial technocrats and the elites who employ them. I met artists concerned with community and connection, and I saw sexy Instagrammers vying to rub shoulders with those who are more socially connected. I saw beautiful art that was ostensibly made for its own sake, and I saw art that appeared to me as art-as-outdoing-the-other. I saw Las Vegas-esque showiness and blue-collar humility. However, for all that, I didn’t see depravity. The debauchery I had half hoped to find wasn’t there. In fact, I saw people approach self-expression and exploration of body and mind in the most responsible and even sacred way I’ve ever seen. And in all my interactions I felt, at minimum, seen, but more often honored. In the end, I saw only good people enjoying themselves and each other’s company. Even the accused gentrifiers, whom Burning Man veterans and left-leaning media have berated in recent years, danced with open arms and RV doors.

What you see in the media is not what makes Burning Man a transformative experience. It is not the neon-saturated desert night, the glistening skin of sinewy 26-year-olds, the dusty surreality, or the art, drugs, and sex that transport the mostly middleclass white citizenry (another feature of Burning Man that naysayers love to contest) to heaven on earth. Rather, these elements of Burning Man facilitate the emergence of an entrenching community. And that is where transformation lies.

I was lifted up at Burning Man not by the psilocybin buzzing through my head, but by my neighbor who practiced scales on his saxophone at one a.m.; by my newfound Filipino brothers who slurped noodles and sipped Glenfiddich with me under crystalline stars; by the Australian couple who scrubbed my back amidst twenty-five other naked people at the public dance-shower, then joined me in my tent to wait out a dust storm and munch pumpkin chocolate chip cookies; by that one guy who belted “Where the Streets Have No Name” through a PA system mounted to an art car as though his entire life had been leading up to that moment; and by the general sharing of food, booze, hugs, and conversation.

Why isn’t life in the real world—or, as burners like to call it, the “default world”—just as communal? Is it the size of our cities? Seventy thousand people living harmoniously for eight days seems to suggest not. Is it that we don’t imbibe permagrin-inducing drugs on a daily basis? Antidepressant prescription rates suggest we are hardly drug free. (Maybe antidepressants are just inferior drugs.) Is it the myth of the efficacy of money?

Perhaps I’m being trite. Such questions are not easily answered. Burning Man, despite being promoted as a “temporary city,” complete with its own census, is fundamentally a festival—a festival unlike any other no doubt, and city-like in scale, but still a festival. So it’s difficult to judge whether Burning Man’s mores could spawn a thriving, socialist metropolis. Still, there is something to be revealed in Burning Man’s moneyless concourse.

When you need something in Black Rock City, whether food, fuel, or fresh batteries for your ghetto blaster, you don’t drive to the nearest superstore and satisfy your needs via a hollow exchange with an underpaid cashier; you humbly beseech your neighbors. But because the culture encourages self-reliance, radical inclusion, and unquestioned gifting, it is seldom that you need ask for help, and just as seldom that you get solicited. Instead, people share generously, sometimes because they perceive a need in their fellow burner, but more often for the joy of giving and cultivating community.

I recognize I may be romanticizing this point, for burners must’ve paid, at some point, for all their supplies with cold, hard cash. Then again, many burners are DIYers and make efforts to support grassroots and community businesses and ventures. But whether or not burners are morally consistent in the way they approach commerce in the default world and how they interact on the playa is not the point. The point is the demonstration: that Burning Man’s moneyless culture is precisely what causes community to flourish.

There aren’t even proper words to describe a robust moneyless culture. The synonyms for “moneyless” are “bankrupt,” “impoverished,” “indigent,” “insolvent,” “penniless,” and “poor.” But Black Rock City is rich, vibrant, and alive. At Burning Man, there is no pursuit of “success,” nobody asks “so, what do you do?” and the most virile form of currency, if I can call it that, is contribution. So unlike a capitalist society, where what we consider praiseworthy and purchase-worthy often conflict, leaving social programs defunct and consumer culture high on the hog, on the playa, what we revere and what prospers coincide—like art, love, and community.

Again, this was demonstrated in part, just as in part I saw what seemed, to me, like overconsumption. Also, though most of my communal experience at Burning Man felt wholly honest and organic, there were aspects that felt contrived. But maybe I just have more to learn.

During all my time at Burning Man I never felt judged. I never heard burners speak of rich gentrifiers or non-contributing virgins—and not because they’re unaware of their changing culture. Still, I heard no complaints, and I suppose I have none myself—except that I didn't attend five years ago, because I sense it was a different Burning Man then.

Since returning home I’ve wondered whether I’m part of this so-called gentrification. I’m a middleclass white male who detests yet profits from American consumerism (not by choice, I tell myself), and I invaded an alternative community in search of more honest connection. But I feel like I did it right: I packed minimally, I shared my talents and my resources, and I made art in the way I know how. And, let's be honest, I partied heartily, too.

But suppose I am one of these unwanted gentrifiers. Why, then, did I feel so at home? Why did I feel like I had found my own kind? Why, on my final day at Burning Man, was I ready to proudly accept the playa name I had been given? Radical inclusion, right? Which, if we're practicing, ensures even Silicon Valley rich kids are welcome (or Silicon Slopes kids, as in my case).

So, will I attend Burning Man again? That is the question I have been asked more than any other. To which I reply, “Ask me next August.”